National Emergency Powers Trump Border Wall

The President Trump has said he would consider invoking emergency powers to build a wall on the southern border, an extraordinarily aggressive move almost certain to invite a court fight.

According to the budget stand between President Trump and congressional Democrats grinds into the third week of a partial government shutdown, the White House has floated the idea that Mr. Trump might invoke emergency powers to build his proposed wall on the Mexican border without lawmakers’ approval.

That route could resolve the immediate crisis by giving Mr. Trump a face-saving way to sign spending bills that do not include funding for his wall. But it would be an extraordinarily aggressive move — at a minimum, a violation of constitutional norms that would most likely thrust the wall’s fate into the courts. Here is a primer on whether Mr. Trump can use emergency powers to proceed with the project without explicit congressional permission.

The president has the authority to declare a national emergency, which activates enhancements to his executive powers by essentially creating exceptions to rules that normally constrain him. The idea is to enable the government to respond quickly to a crisis.

Although presidents have sometimes claimed that the Constitution gives them inherent powers to act beyond ordinary legal limits in an exigency, those claims tend to fare poorly when challenged in court.

But presidents are on firmer legal ground when they invoke statutes in which Congress delegated authorities to the executive branch that can be generated in emergencies. In a recent study, the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law identified 123 provisions of law granting presidents a range of such powers.

The National Emergencies Act, enacted during the post-Watergate reform era, regulates how presidents may invoke such powers. It requires them to formally declare a national emergency and tell Congress which statutes are being activated.

The Trump administration could point to two laws and say they allow officials to proceed with building a border wall without first obtaining explicit authorization and appropriations from Congress, according to Elizabeth Goitein, who oversaw the Brennan Center’s study and is a co-director of its Liberty and National Security Program.

One of the laws permits the secretary of the Army to halt Army civil works projects during a presidentially declared emergency and instead direct troops and other resources to help construct “authorized civil works, military construction and civil defense projects that are essential to the national defense.”

Another law permits the secretary of defense, in an emergency, to begin military construction projects “not otherwise authorized by law that are necessary to support such use of the armed forces,” using funds that Congress had appropriated for military construction purposes that have not yet been earmarked for specific projects.

In light of those statutes and similar ones that give presidents flexibility to redirect funds in a crisis, the Trump administration could point to serious arguments to back up Mr. Trump if he invokes emergency powers to build a wall, said William C. Banks, a Syracuse University law professor who helped write a 1994 book about tensions between the executive and legislative branches over security and spending, “National Security Law and the Power of the Purse.”

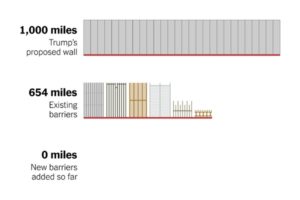

The Border Wall: What Has Trump Built So Far?

The existing barrier isn’t a single mile longer than it was when he took office. The fundamental principle is that no president or official may spend funds that were not appropriated for that purpose,” he said. “But I think that it’s possible that the president could declare a national emergency and then rely on authority Congress has historically granted for exigencies to free up some funds to support constructing a barrier along the border.

Mr. Trump is almost certain to invite a court battle. While Ms. Goitein agreed that “there is a nonfrivolous legal case to be made” that emergency-powers laws might empower Mr. Trump to spend military funds on a wall, she also pointed to counterarguments any lawsuit would have to contend with.

For example, she noted, under one of the laws Mr. Trump might try to invoke, the military may redirect funds to build only projects that Congress has separately authorized. Lawmakers have not approved a military wall spanning the border.

Still, the administration might argue that Congress has effectively preapproved a wall-like barrier under other laws, including one that authorizes the militaryto construct border “fences” blocking drug-smuggling corridors, and another, the Secure Fence Act of 2006, that empowers the Department of Homeland Security to build “physical infrastructure enhancements” along the border.

The government could skip the requirement to identify pre-existing authorization for a wall if it invoked a different emergency-powers law for the funds, but that route would raise other problems, Ms. Goitein said. Among them, the government would need to show that a wall meets the legal definition of military construction even though it is not clearly tied to a military facility or installation and that the southern border situation represents the kind of emergency that requires the use of the armed forces.

If Mr. Trump declares that the situation along the southern border suddenly constitutes an emergency that justifies building a wall without explicit congressional sanction, he will run up against a reality: that the facts on the ground have not drastically shifted. The number of people crossing the border unlawfully is far down from its peak of nearly two decades ago. The recent caravans from Central America primarily consist of migrants who are not trying to sneak across the border but instead are presenting themselves to border officials and requesting asylum.

And while Mr. Trump and his aides keep claiming that terrorists are sneaking in across the border, including assertions that they are doing so by the thousands, as a matter of empirical reality, there has been no such instance in the modern era.

Still, as a matter of legal procedure, facts may be irrelevant. Before a court could decide that Mr. Trump had cynically declared an emergency under false pretenses, the court would first have to decide that the law permits judges to substitute their own thinking for the president’s in such a matter. The Justice Department would surely argue that courts should instead defer to the president’s determination.

“If any court would actually let itself review whether this is a national emergency, he would be in big trouble,” Ms. Goitein said. “I think it would be an abuse of power to declare an emergency where none exists. The problem is that Congress has enabled that abuse of power by putting virtually no limits on the president’s ability to declare an emergency.”

Why did Congress give presidents such broad power?

In part by accident. When passing many emergency-powers laws, Congress attached a procedure that would let lawmakers override any particular invocation of that authority. The National Emergencies Act, for example, permitted Congress to rescind an emergency if both the House and the Senate voted for a resolution rejecting the president’s determination that one existed.

But in 1983, the Supreme Court struck down such legislative vetoes. The justices ruled that for a congressional act to have legal effect, it must be presented to the president for signature or veto. Because it takes two-thirds of both chambers to override a veto, the ruling significantly eroded the check and balance against abuse that lawmakers had intended to be part of their delegation of standby emergency powers to presidents.